Written by Doug Anderson and Cassie Grenier.

The various party leaders have made a dizzying number of specific policy promises and commitments over the past few weeks. Our research sought to investigate what impact these promises may be having on voters’ willingness to consider each party.

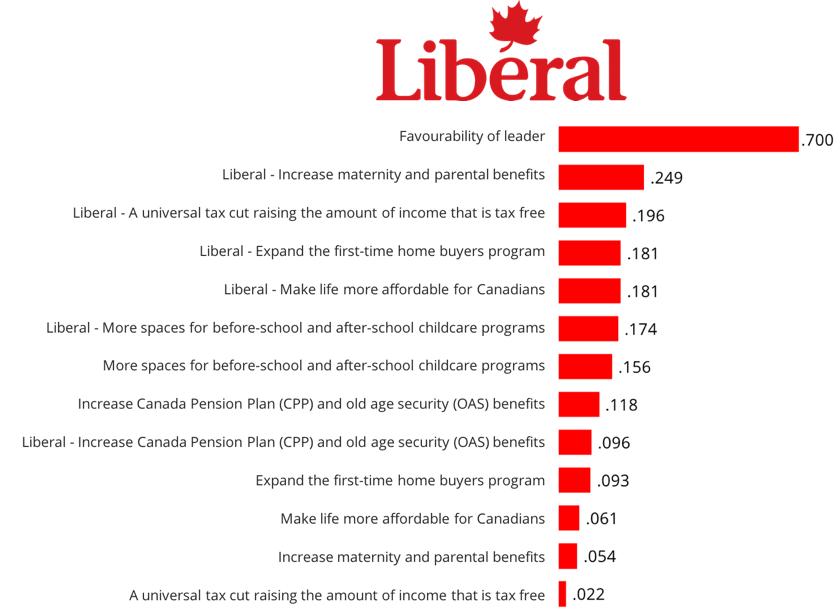

Overall recall of a specific promise from Andrew Scheer, Justin Trudeau or Jagmeet Singh is surprisingly low. For any of these three leaders, at least two-thirds of voters can’t even vaguely recall a specific promise that leader has made. With recall levels that low, it is immediately clear that the promises themselves are at best very narrowly effective. And in terms of how the promises relate to willingness to consider voting for any party, they are much less influential than leadership impressions.

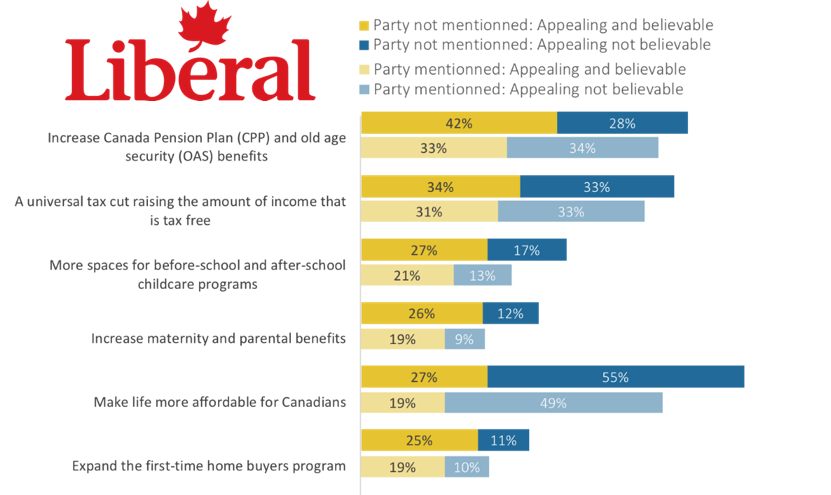

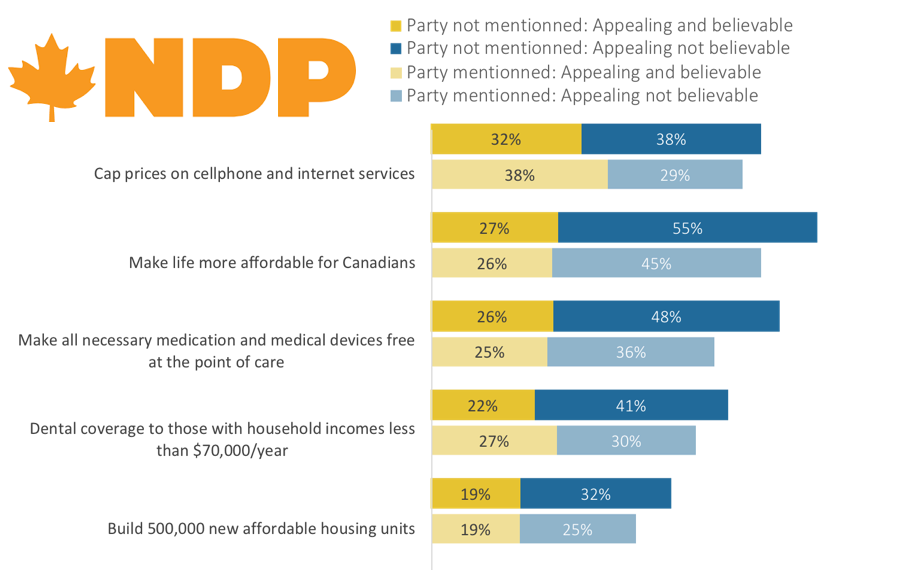

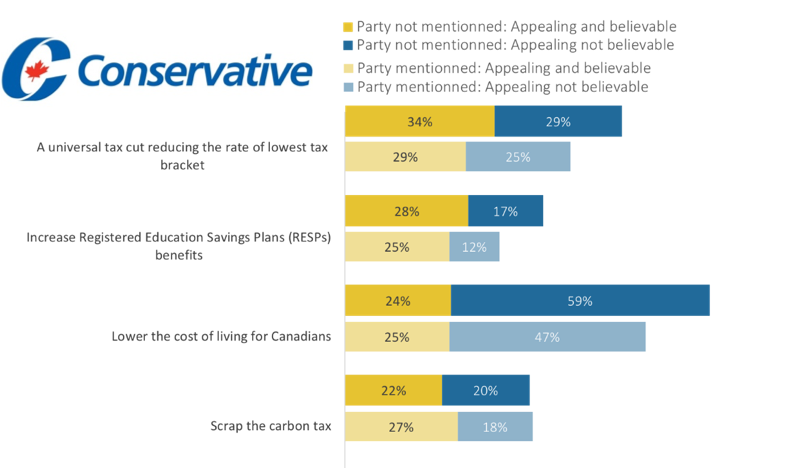

To try to understand whether some promises are more strategically helpful than others, each respondent was provided four or five promises made by each of Scheer, Trudeau and Singh and were asked two questions in each case: how appealing the promise is; and, how believable it is.

For each promise tested, an experiment was conducted. Half of the respondents were shown the promise without mentioning which party made the promise and half the respondents were told which party had made that promise. In total, 14 promises were tested (including one which has been made nearly identically by both the Liberals and NDP: “to make life more affordable for Canadians”). The lists of promises tested for each party were pulled from among those covered by the media during the campaign and selected and described with guidance from Earnscliffe Principals who have an active affiliation with the political party in question.

This investigation produced a number of very interesting findings, shedding light on how promises are being received, perceived and are influencing voting decisions. Presumably each campaign has this kind of information and it will be informing tactical decisions for the home stretch of the race.

First, the inclusion of the brand has a dampening effect on the level of appeal of almost every promise. The single exception was the promise to scrap the carbon tax, which is basically equally as appealing to Canadian voters whether it is cited as a Conservative promise or not. This overall tendency suggests that while some promises may be more broadly appealing than others, the party brand has a mildly detracting effect on the appeal of any promise.

Second, significantly more people find any given promise appealing than find it both appealing and credible. This is true whether respondents are told which party made the promise or not. This is pretty compelling evidence that campaign promises – regardless of which candidate makes them – are not generally taken at face value, even if they have very broad appeal. The degree of drop-off from being seen as appealing to being seen as both appealing and credible seems to be greater for promises that are more vague (e.g., making life more affordable for Canadians or lowering the cost of living for Canadians) and less severe for more granular promises (e.g., increasing RESP benefits). This suggests that the more a person can relate the promise to a specific change, the more they find it credible.

Third, the appeal of each promise varies widely, sometimes holding appeal among far more people than are willing to consider voting for that party. The vague promises are not particularly credible, but they are among the ones with broadest appeal, with strong majorities finding the idea of making life more affordable for Canadians or lowering the cost of living for Canadians to be appealing – regardless of whether the party making the promise is named or not. Among the more clearly defined promises, the range in appeal varies from less than one out of three voters to more than four out of five.

In most cases, the ones with the lowest proportions of appeal tended to be the ones that benefit the fewest Canadians such as those designed to help parents or first-time home buyers. Only one promise purported to help the entire adult population fails to be seen as appealing to the majority of voters: scrapping the carbon tax.

For each party, the nuances of appeal and credibility demonstrate a unique mix of broad and narrow appeal.

For the Liberals, two of the more descriptive, concrete promises performed fairly well. Two in five (42%) found increasing CPP and OAS benefits appealing and believable. When cited as a Liberal promise, ”making life more affordable for Canadians” appeals to the majority of voters (68%), but only 19% find it both appealing and credible. Fully 49% find this promise as made by Liberals to be appealing but not believable.

The Liberal promises that were less tangible such as ”lower the cost of living for Canadians” resulted in the majority of respondents finding it appealing though not believable (59%).

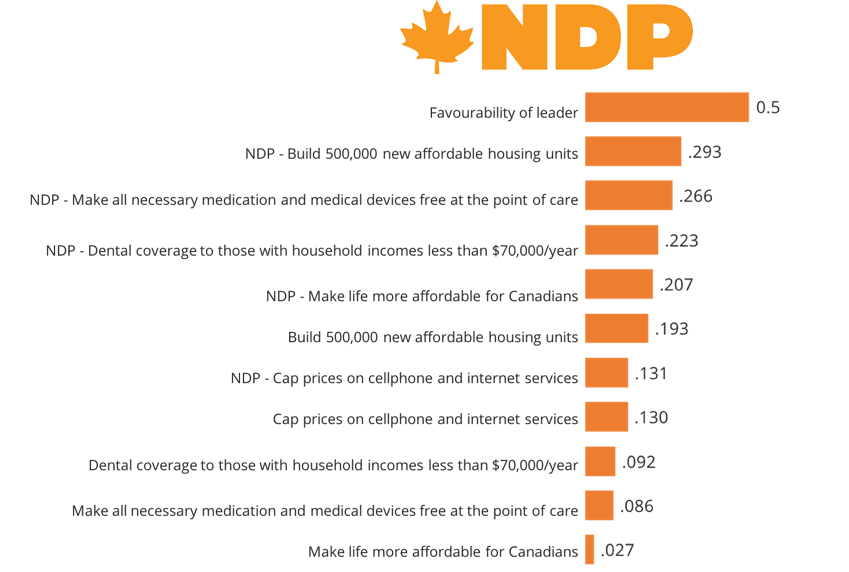

Compared to the Liberal and Conservative commitments tested, the NDP promises performed well. The most appealing and believable promise is capping prices on cellphone and internet services, with a third (32%) of respondents finding this promise both appealing and believable, and another third (38%) finding it appealing though not believable.

The promise to”make life more affordable for Canadians” has been made by both the Liberals and the NDP, so it was tested with both party brands. It was most appealing when tested without either party brand, with 27% feeling it was both appealing and believable, and another 55% feeling that it was appealing and not believable. However, when attributed to one party or the other, it tested better when branded as an NDP promise (26% appealing/believable) compared to Liberal branding (19% appealing/believable).

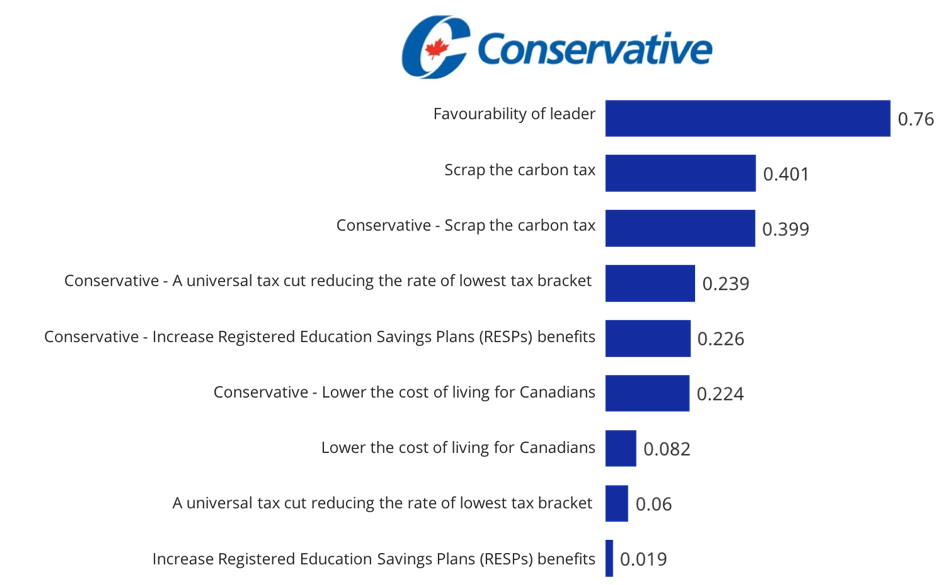

Among the Conservative promises tested, the vague notion of lowering the cost of living for Canadians has the best results. However, while it was appealing to about three quarters (72%) of voters, only 25% find it both appealing and credible. Although not as broadly appealing, the specific promise of a universal tax cut found the highest proportion of voters finding the promises both appealing and credible. That said, the study found nearly identical proportions (25% to 29%) saying any of the four Conservative-branded promises are both appealing and credible.

The results on leadership demonstrated the particularly high correlation between the overall views of a leader and one’s willingness to consider voting for that leader. Our analysis shows that recall of a promise having been made by any leader or the appeal of any of the promises does not come anywhere near the level of correlation with vote consideration that leadership impression has.

The experiment also demonstrates that the appeal of a promise, without any mention of which party proposed it, finds virtually no correlation with vote consideration. The single exception is the promise to cut the carbon tax, which has roughly the same correlation with Conservative vote consideration whether the party is named or not. This begs many questions and some hypotheses emerge that may merit future investigation. For example, it suggests that the party brand drives the correlation with vote more than the promise itself. The fact that the carbon tax promise is the one exception may be an indication that it is the only promise that people fairly readily and accurately pair with the specific party making that promise.

Certainly, the data suggest that the flurry of promises are, at best, contributing only a small influence on voting consideration. The fact that so many Canadians cannot recall any specific promise made by any party is damning evidence of how hard it is for any promise to cut through the clutter and resonate with voters. The fact that brand mention is required to find a correlation with vote consideration suggests our questionnaire may have provided voters surveyed with more information about who the promises come from than they already had.

This research also suggests a brand paradox facing party communications strategists. Party brand tends to detract from the appeal of almost every promise, but without making sure people associate the brand with the promise, the promise does nothing to influence vote. Therefore, the only rational approach is to try to make sure the appealing promises are branded in people’s minds in order to get some benefit in terms of voter engagement.

Earnscliffe is pleased to present the results of our latest survey of the Canadian electorate. In this Special Bulletin of Earnscliffe’s Election Insights, we share insights on what could still happen in this election; how to leverage leadership; and, how (if at all) voters are considering the parties’ electoral promises.

In the coming days, we will share further insights on the issues influencing voters’ choices as well as other topics covered in the survey.

About our survey (Methodology): The results are based upon an online survey of 1,756 eligible Canadian voters randomly recruited through the use of the Leger Opinion (LEO) online panel. The survey was conducted between October 1st and 6th, 2019. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to age, gender and region in order to ensure sample reflective of the population. As this was a non-probability sample, no margin of error can be associated with the results, nor is it appropriate to offer any comparative margin of error indicating the level of accuracy of results had the study been conducted using random probability sampling.