Earnscliffe survey shows that half of voters hold opinions that are preconditions for electing populists.

Populism has rapidly become a cultural force causing enormous change in the political landscape of democracies all over the world. As a result, the term has dominated political dialog for the past few years, but it’s also a term that has been appropriated to mean all kinds of things – from nativism, to the politics of polarization to the “prairie populism” of Tommy Douglas — making it difficult to reach a consensus definition.

The Oxford Dictionary defines populism as “a political approach that strives to appeal to ordinary people who feel their concerns are disregarded by established elite groups.” So for now, let’s settle for that.

In order to avoid unnecessary hysteria, it is important to remember that the negative connotations that are associated with populism today are not found in all cases of populism. As Canada has shown a number of times in its brief history, populism can be a force for the kinds of progressive changes that societies come to cherish. Populism can arise within any ideology and is certainly not a tendency exclusively found among the right or left of the political spectrum. Populism is not necessarily even always bad or always good and that judgement may depend on the eye of the beholder.

The sorts of populism that have risen recently in Hungary, Brazil, Italy, the Philippines and elsewhere, and the better recognized populist antecedents driving the election of Donald Trump in the United States and Brexit in the UK include some of the more worrying traits and have caused many to wonder if Canada may be part of the same electoral trend and further, whether there is reason to be concerned if that were to happen. To explore this question, Earnscliffe conducted an in-depth nation-wide study of political attitudes that tests the extent to which Canadian embrace populist sentiments, who is most likely to hold these views and why.

The results of Earnscliffe’s survey demonstrate that half (50%) of Canada’s voters hold attitudes that make them open to populist exhortations, including one in four (25%) who appear to embrace the fundamental views necessary for populism to flourish.

For populism and populists to find support, there needs to be an environment of distrust in politicians and institutions, a feeling that government serves interests other than those of “the people,” a sense of frustration over the direction of government and a sense of fear of being “left behind” in a changing world.

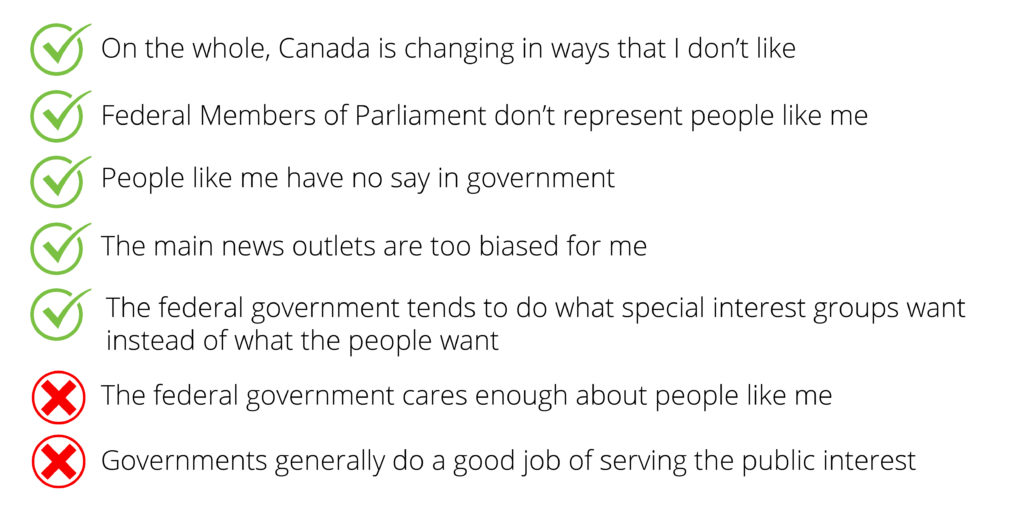

In order to identify the inclination of Canadians to gravitate towards a populist candidate, we measured the level of agreement and disagreement to seven specific statements that tap into various aspects of populist sentiment:

To develop an index that places Canadians along a “populist spectrum”, every respondent was assigned a rating between 0 to 7 depending upon how many of these views they hold; 0 indicating that an individual espouse no populist views whatsoever and 7 indicating absolute adherence to all populist viewpoints.

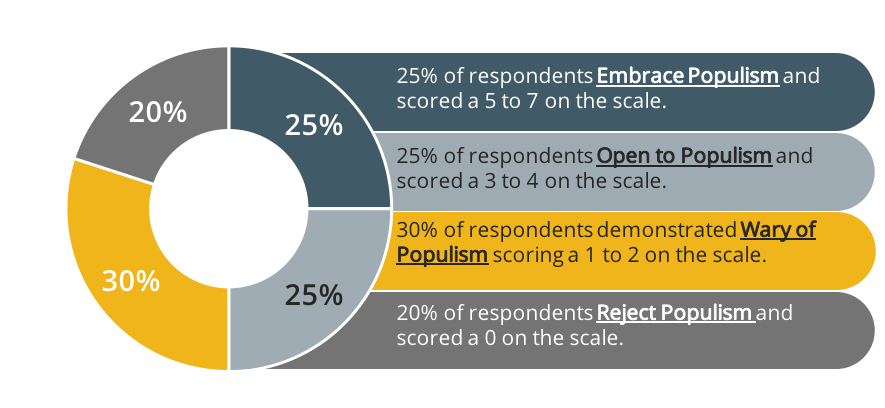

What the results show is that there are very few Canadians who could be described as rock-ribbed, pure populists – only 4% of the population agree or disagree with all populist attitudes and score a “7” on the spectrum. On the other side of the ledger, 5 times as many – or 20% – express no populist views whatsoever and score a “0”. Indeed, fully 35% of Canadian voters score “1” or less on the populist spectrum, basically confirming the traditional characterizations of Canadian political culture as embracing pluralism and accepting government as an agency of public good and not evil.

But as with all things Canadian, further analysis indicates that the populist landscape is a little more nuanced than conventional wisdom might suggest. While the overall tenor of Canadian’s world view can be best characterized as rejecting populism, 80% of the population agree or disagree with at least one of these indicators of populism and a quarter of all voters score at least “5” or more and consequently are decidedly more populist than satisfied with how Canadian democracy reflects their interests. So while it is clear that populism is not a dominant feature of Canadian political thought, strains of populism, to varying degrees, exist in Canada as elsewhere.

To better understand which segments of the population were most – and least – likely to embrace populism, we then collapsed the spectrum into four quadrants:

Using this methodology, here is what we found:

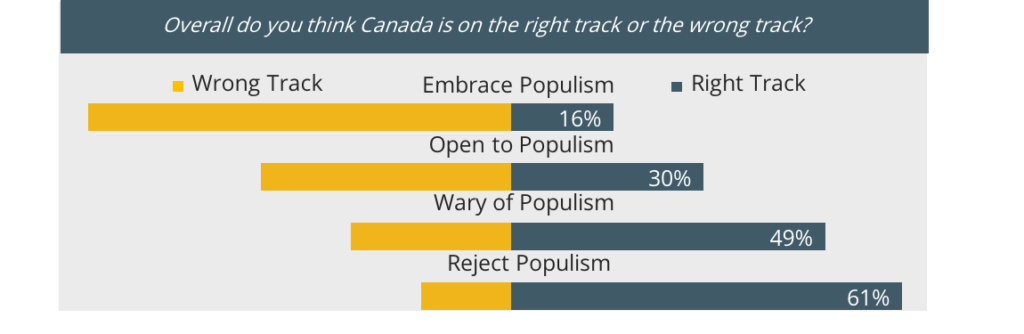

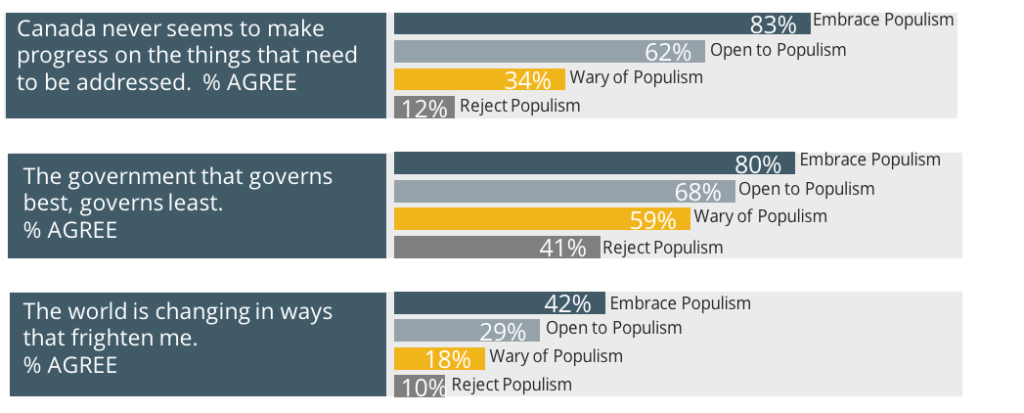

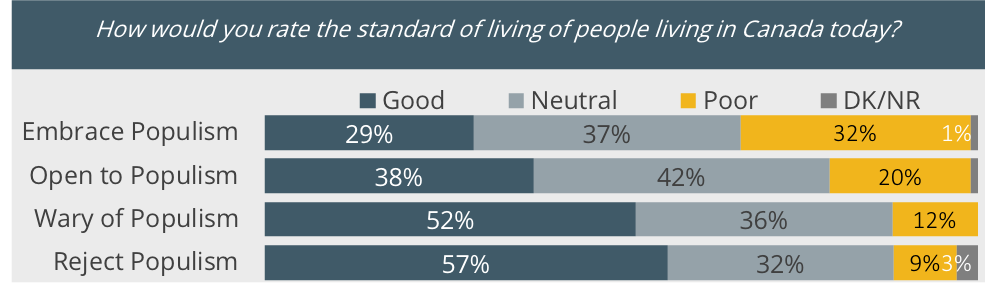

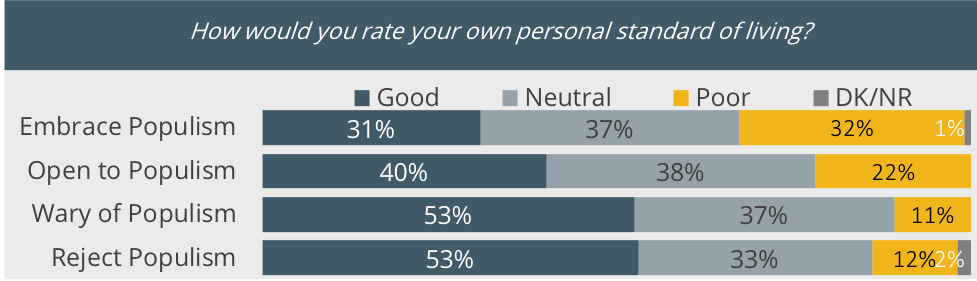

First, populism is fueled by an unhappiness with the direction that society is headed in and particularly as it is being directed by government.

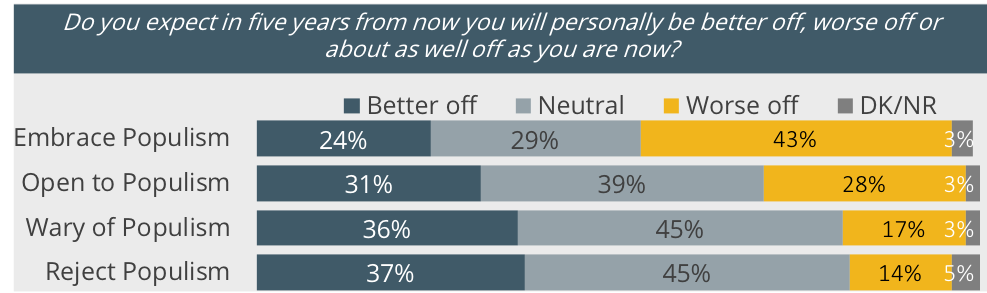

Second, a willingness to embrace populism is also rooted in a belief that I, and others like me, are not and will not be thriving in this changing world.

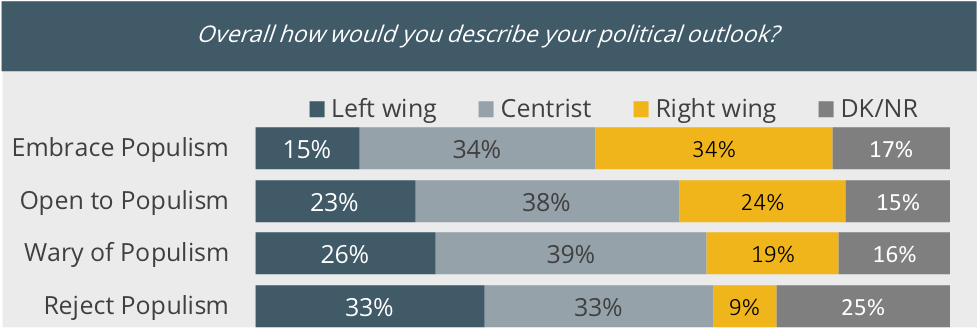

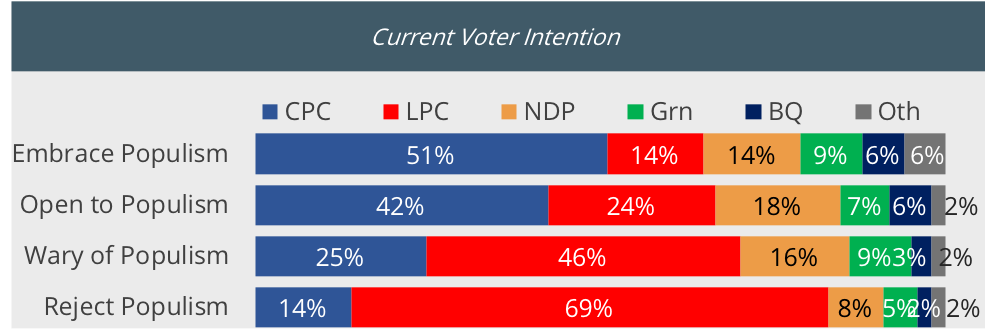

Populism also manifests itself in political outlook and partisan preference. However, while its presence definitely skews along a right-left spectrum, populist sentiment effects Liberal and Conservative fortunes but not the NDP’s.

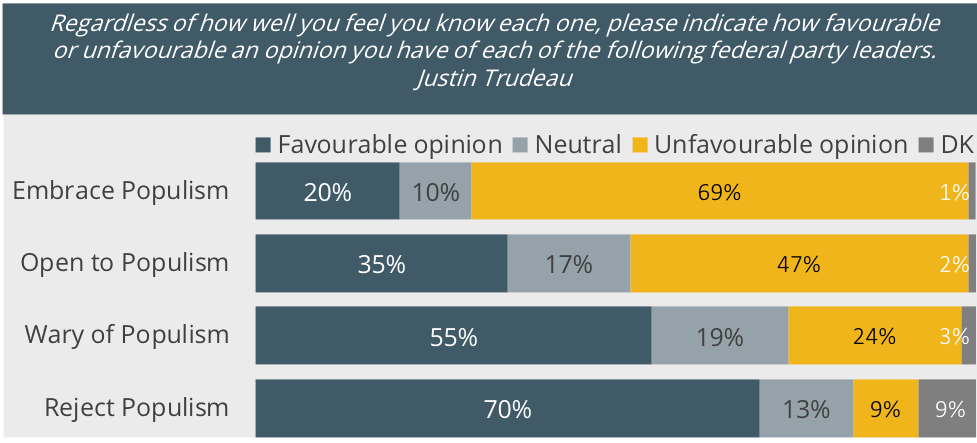

At a more personal level, Prime Minster Trudeau is particularly polarizing depending on where you find yourself along the Populism Spectrum.

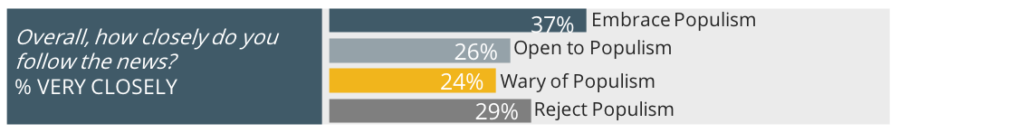

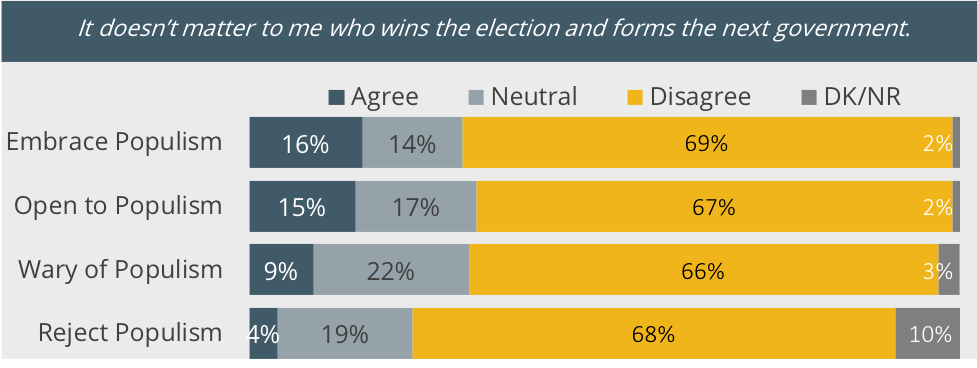

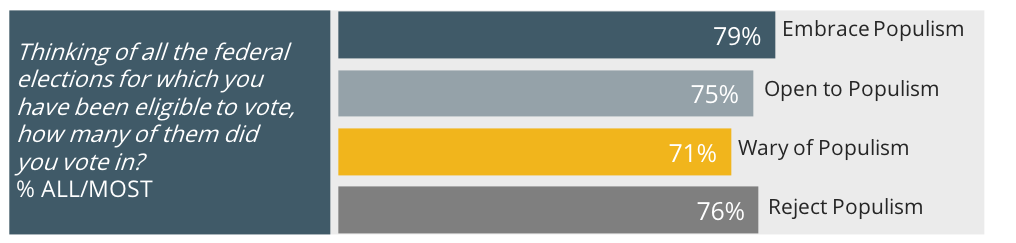

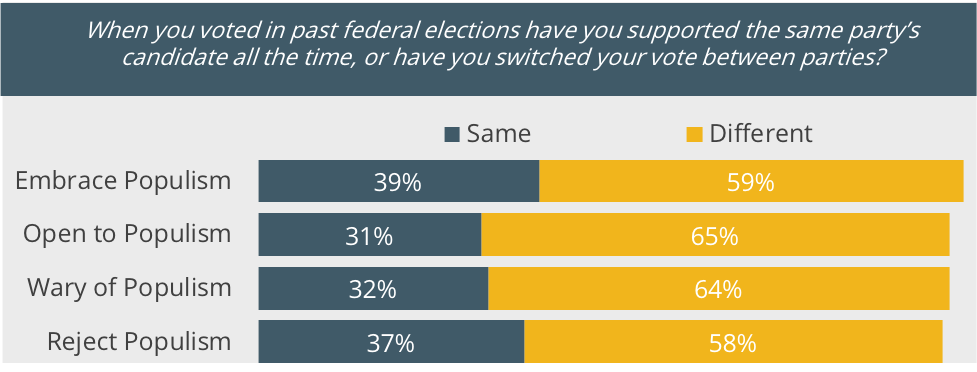

Populists however are not marginalized, alienated by-standers. They are engaged, involved and participate in the political process and believe they have every bit as big a stake in election outcomes as those who reject populism and are content with how democracy is serving Canadians.

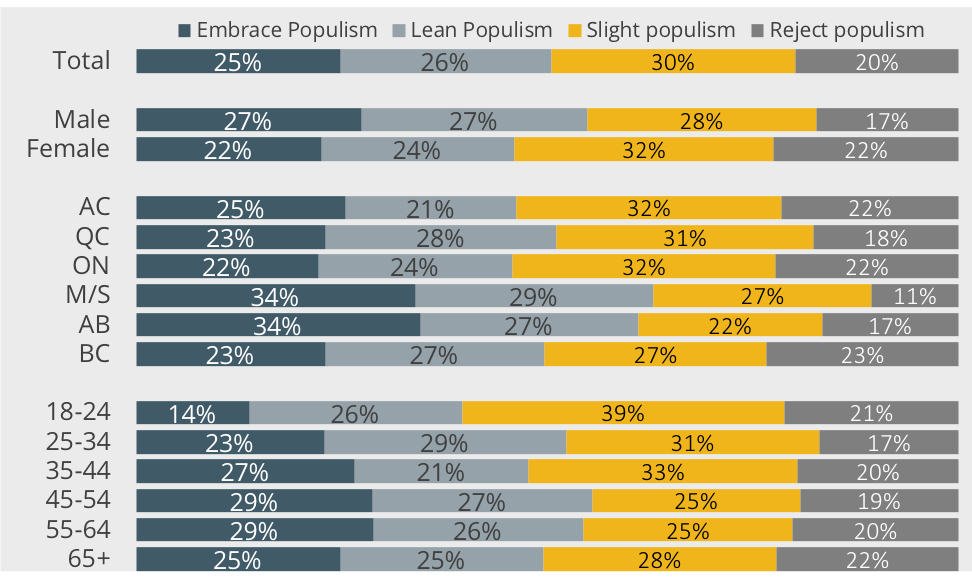

Voters who express populist views can be found in every region and every age group, although the incidence is decidedly higher on the Prairies and slightly higher among men and middle-aged voters.

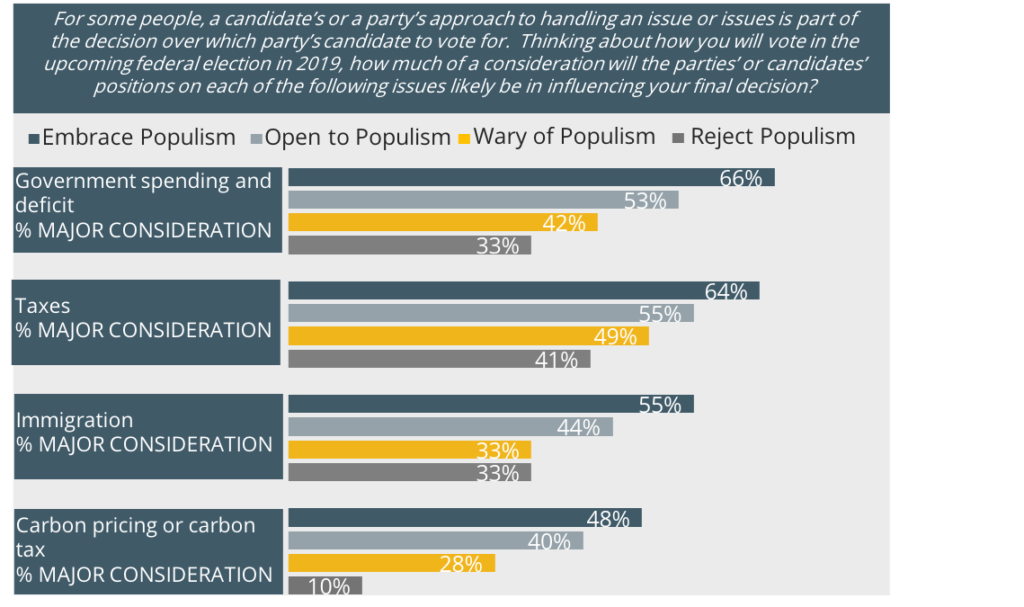

Populists also appear to be more motivated and galvanized by policy. Their votes are most likely to be influenced by issues that touch on spending and deficit, taxation, immigration and carbon pricing.

“Looking at these findings it seems pretty clear that populism does not happen by accident”, said Earnscliffe Principal, Allan Gregg. “It finds its roots in the soil of discontent – in a belief that society is changing in such a way that some are being left behind and that those who are entrusted with protecting the vulnerable from these vagaries, either don’t understand them or don’t care about them. That soil is then tilled by political leaders who fail to understand the growing disconnect between these voters and those who govern, and – as we have seen in other jurisdictions – the seeds of populism can grow fear and resentment towards ideas and others that represent, or actually may be benefiting from this unwelcomed change.”

“Through a combination of good luck and good policy, Canada has been able to avoid much of this kind of polarization and ugliness. A fairly strong and universal social safety net, a world class public educational system and a history of diversity and ethnic co-existence has meant that most Canadians have had little reason to pit their interests against those of their fellow citizens. But make no mistake. When it comes to equality, prosperity and anticipating the future, Canadians are polarized. Today, fully two thirds of Canadians believe that they will be no better (39%) or even worse off (26%) in 3 to 5 years than they are now, while a third see themselves flourishing in the near future. This suggest that Canadians are responding to a changing word in vastly different ways.”

“As we have seen from this study, voters who express populist sentiments are engaged, they are moved by issues and they do not appear willing to sit back passively and defer to either their leaders or the status quo. So if we want to avoid the fate of the Hungarys, Brazils, Philippines and even our neighbours to the South and maintain Canada as “the peaceable kingdom”, our elected leaders would be well advised to listen more carefully to the voices of discontent.”

Methodology: The results are based upon an online survey of 2,427 eligible Canadian voters randomly recruited from LegerWeb’s online panel and conducted between January 25th to February 5th, 2019. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to age, gender and region in order to ensure sample reflective of the population. As this was a non-probability sample, no margin of error can be associated with the results, nor is it appropriate to offer any comparative margin of error indicating the level of accuracy of results had the study been conducted using random probability sampling.