Written by Velma McColl. Published by Policy Magazine.

We’re at the midway point of COP26 in Glasgow. Some 130 global leaders have come and gone and put their best cards on the table. What happens over the next week will be left to ministers and climate diplomats, an invisible and often unsung group of officials who propose the rules in backrooms and establish the global governance for how we address and manage greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions well into the future.

Except that it was well established at the failure of COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, governments alone can’t achieve 2, never mind 1.5 degrees Celsius and so what’s happening inside the Scottish Event Campus isn’t the whole story. It also explains why every day there are starkly contrasting social and media narratives coming out of Glasgow.

Looked at through one lens, there’s a mind-boggling set of accomplishments since Sunday to move the world to net-zero by 2050: unprecedented global agreements on deforestation, $100 billion in public finance, $130 trillion in private finance; global efforts to accelerate the energy transition including permanently limiting the use of coal for electricity, ending fossil fuel subsidies, breakthroughs in investment in electrifying transportation, renewables, hydrogen, and negative emissions.

Not to overlook social and cultural highlights recognizing youth, women (UN figures show 80 percent of those displaced by climate change are female) and Indigenous voices that have begun to successfully weave their earth-focused worldview into the negotiations and agreements.

Well done, we might say. Good job at challenging a number of energy and economic status quo systems all at the same time. The kind of global cooperation we only dreamed of when we signed the Paris Agreement in 2015, after fighting for 20 years against the conventional wisdom that it simply wasn’t possible to overcome the narrow national interests of 196 countries and act together in the interests of our one planet.

From another lens though, there is failure, a lack of ambition to do enough, fast enough to limit temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030. There are the criticisms around the lack of inclusion of enough voices from the global south, enough urgency to save Small Island Developing States (SIDS) from drowning in rising ocean tides. There are the audacious voices of four young women – Greta, Vanessa, Dominika, Mitzi – whose global call to youth and their parents has yielded 1.7 million signatures so far. Their petition looks for real action against a climate emergency, calling for some of what leaders are focused on and they want it with more inclusion, more fairness and less bureaucracy.

On Saturday, there will be a march that will attract thousands of people in Glasgow, all across the UK and around the world to say, “Not enough. Not fast enough. Make a difference for your children and your grandchildren.”

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, then here are two pictures that help capture the difference in the contrasts described above. The first is the “family photo” from world leaders and the second is the youth panel hosted by the New York Times this week. For an intergenerational issue, these images underline some of the reasons for the tension and competing narratives.

Brené Brown, the plain-spoken Texan and compelling social researcher, talks about cognitive dissonance as “the psychologically painful process of trying to hold two competing truths in a mind that was engineered to constantly reduce conflict and minimize dissension.”

For me, like many of us standing in the midst of all this creative tension, we are living with the contradictions. COP26 is rich with cognitive dissonance and yet in order for us as a planet to do this extraordinarily hard thing to reverse the effects of climate change in a generation, we’re going to have to live into the tension, feel how uncomfortable it all is and hold those two tough-as-nails things to be true, at the same time. We can be both doing more than we have ever done before and not doing enough.

Brown has also spoken about the discomfort of FFTs or “f&%@ing first times.” Her research shows that when we experience something that we’ve never lived through before, it triggers all our fight, flight or freeze instincts. The result? We want to get reductive and see only all good or all bad. We’re going to bump into the very human problem of wanting to label things as complete victory or an absolute failure. Watch for these declarations on either side from media, political, business and civil society voices over the coming days.

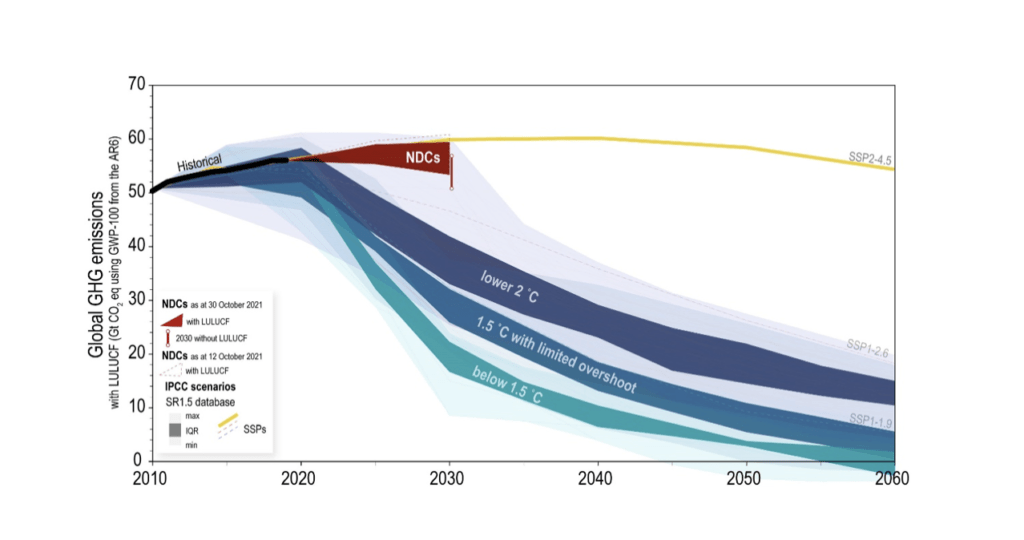

In all these human dynamics, we have to learn the lesson of COVID-19 and return to the science and the math. In a system that has been created since the Paris Agreement, the UNFCCC now does a synthesis and real-time accounting on how all the commitments registered with the UN stack up against the Paris targets.

We’re going to bump into the very human problem of wanting to label things as complete victory or an absolute failure. Watch for these declarations on either side from media, political, business and civil society voices over the coming days.

With all the ballyhoo from leaders this week, as of November 4th, the numbers show that there is a 13.7 percent increase in global GHG emissions by 2030 from 2010 levels. It’s worth noting that many countries’ commitments are measured against reductions over 2005, rather than as 2010 shown in this chart – but, bottom line, we’re not yet on track to meet our 2030 targets. And if we get a slow start to 2030, the cost of reductions to meet net-zero by 2050 will be much more expensive.

And so, the urgency inside and outside the centre going into the final week. Talks in the days ahead will focus on adaptation, more technology advances and defining the Paris Rulebook that will establish fairness in how emissions are counted and on trading and credit systems to support the financing mechanisms.

There’s no getting away from the massive scale of the challenge across our societies and economies needed to address climate change. The UK is hosting a messy, imperfect climate summit here in Scotland, like all the ones that have gone before. If we are to thrive on this one blue planet of ours, we’re going to have to get good at doing a bunch of hard things, together, at the same time, around the world.