Written by Doug Anderson

We may trust the ones we vote for, but rarely politicians in general

Canadians heard the prime minister talk recently about an “erosion of trust” between a minister and his office, but the phrase also describes a general public trend relating to politicians and their esteem among voters. Even before the SNC-Lavalin issue rose to prominence, Canadians had significant trust challenges with politicians.

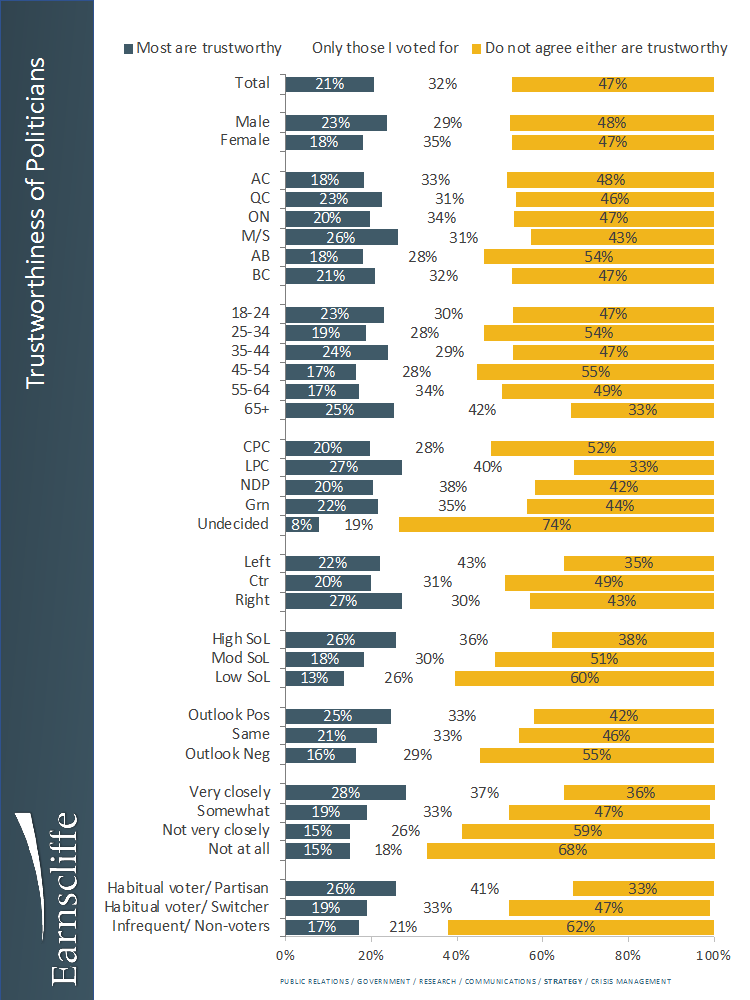

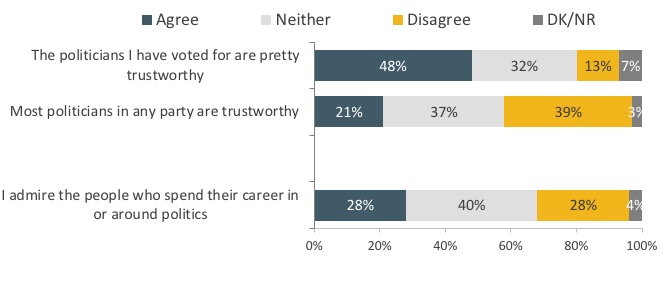

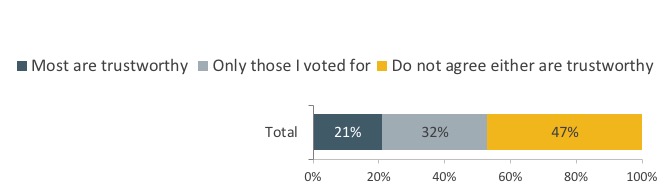

A survey conducted by Earnscliffe in late January and early February offers insight into what the “pre-SNC benchmark” opinion of Canadians was just a few weeks ago. It paints a picture of a society in which only one in five voters (21%) feel “most politicians are basically trustworthy” and roughly one third of voters (32%) feel that only the politicians they vote for are trustworthy. The other half of Canada’s voters (47%) feel that neither most politicians generally, nor even just the ones they vote for, are trustworthy. Furthermore, admiration for people who spend their career in or around politics comes in at only just 28% – marginally more than one quarter of Canadian voters.

“We’ve known for years that the rather generalized concept of ‘trust in politicians’ has been declining, but it is very helpful, and perhaps encouraging to see that Canadians do not necessarily mean ALL politicians. By asking multiple questions around the issue of trust in politicians, it’s pretty clear that there’s more nuance to Canadian opinion than that. It may be surprising to learn, but it turns out that half of those voters casting ballots, actually walk out of their polling station feeling they’ve voted for someone trustworthy,” noted Earnscliffe principal Doug Anderson, one of the lead researchers in this study.

Among Canadians who support a particular party over others, Liberal supporters are the most likely to feel most politicians are trustworthy (27%). Conservative supporters are slightly less likely than other partisans to trust any politicians – whether they vote for them or not – but no partisan supporters are as mistrusting as undecided voters. Fully three quarters (74%) of undecided voters say that neither politicians in general, nor the ones they vote for, are trustworthy.

Notably, these sentiments vary little by gender or region, with the exception of two segments of the population: Canadian voters 65 years of age or older demonstrate a much higher level of trust in both most politicians (25%) and the ones for whom they have voted (42%); and voters in Alberta are least likely to place trust in any politician.

One’s personal outlook for the future and one’s sense of one’s own standard of living positively correlate with trust. The more one feels optimistic about their future or the higher they rate their own standard of living (SoL), the more likely one is to feel politicians are trustworthy.

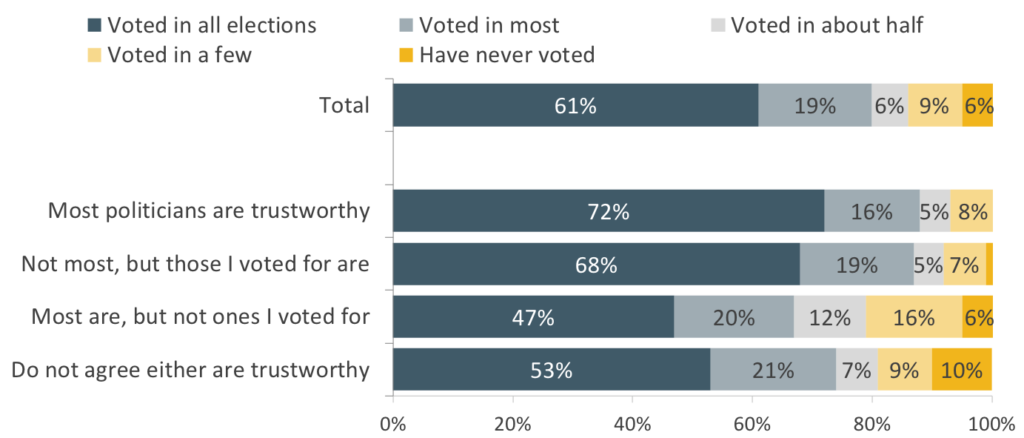

The research also reveals a fairly robust correlation between trust and both how closely one follows current events and how often one participates in elections.

Taken together, these findings suggest that trust (or the lack of trust) in politicians is very much related to how engaged an individual is. The interesting thing about this observation is that it is not just political (i.e. voting) or civic (i.e. following current events) engagement that engenders trust. Trust is also correlated with socio-economic status (whether you are prospering or falling behind) and outlook (whether you are optimistic – and have something to look forward to – or pessimistic – and are looking backward).

This multi-tiered correlation therefore begs a pretty fundamental question, is trust (or a lack thereof) a function of engagement (politically, economically, civically or emotionally) or is engagement a function of trust (in those we should count on to represent and protect us)? We can choose to follow the news or participate in elections, but we don’t choose our socio-economic status or station in life. Given this, the direction of the relationship between trust and engagement is probably the former rather than the later. This in turn suggests that trust can not only be lost, it can also be earned. In other words, the more our politicians address inequity, and give voters a sense that they are engaged in society generally (that voting has meaning, that current events affect them and that they have something to look forward to) the more trust can be repaired.

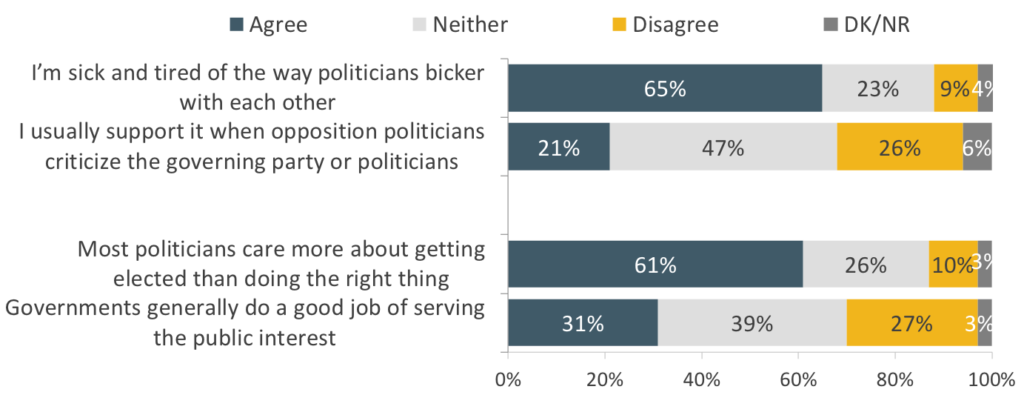

On a related vein, voters clearly continue to want more constructive behaviour from their politicians than they usually see. Most voters say they are sick and tired of how politicians bicker with each other, and few welcome it when opposition politicians criticize the governing party or politicians – however, that’s not because they feel governments generally do a good job of serving the public interest. The majority feel that most politicians care more about getting elected than doing the right thing.

Additional research will be required to gauge whether recent political events will have caused any change to these political trust ratings – for the better or for the worse. These pre-SNC-Lavalin controversy data provide an important baseline.

“An ability to place trust in more than one candidate on a ballot is vital to maintaining a healthy and respectful democracy. When that trustworthiness becomes extremely polarized, or worse – non-existent – the door opens to other problems such as the quest for an ‘authentic’ politician like a populist. All too often, the search for that authenticity attracts regrettable candidates. Canada is as susceptible to that as any modern democracy,” says Earnscliffe’s Allan Gregg.

Methodology:

The results are based upon an online survey of 2,427 eligible Canadian voters randomly recruited from LegerWeb’s online panel from January 25th to February 5th, 2019. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to age, gender and region in order to ensure sample reflective of the population. As this was a non-probability sample, no margin of error can be associated with the results, nor is it appropriate to offer any comparative margin of error indicating the level of accuracy of results had the study been conducted using random probability sampling.

Questions referenced in this release:

Please indicate how strongly you agree or disagree with each of the following statements:

- It’s vital that Canada elects a particularly strong leader in the next election

- I find Canadian federal elections very interesting

- Most politicians in any party are trustworthy

- The politicians I have voted for are pretty trustworthy

- Most politicians care more about getting elected than doing the right thing

- I admire the people who spend their career in or around politics

- Governments generally do a good job of serving the public interest

- I’m sick and tired of the way politicians bicker with each other

- I usually support it when opposition politicians criticize the governing party or politicians